Taking the Earth’s Temperature Over the Past 485 Million Years

New Study Underscores Influence of Carbon Dioxide and Perils of Unprecedented Rate of Human-Made Warming

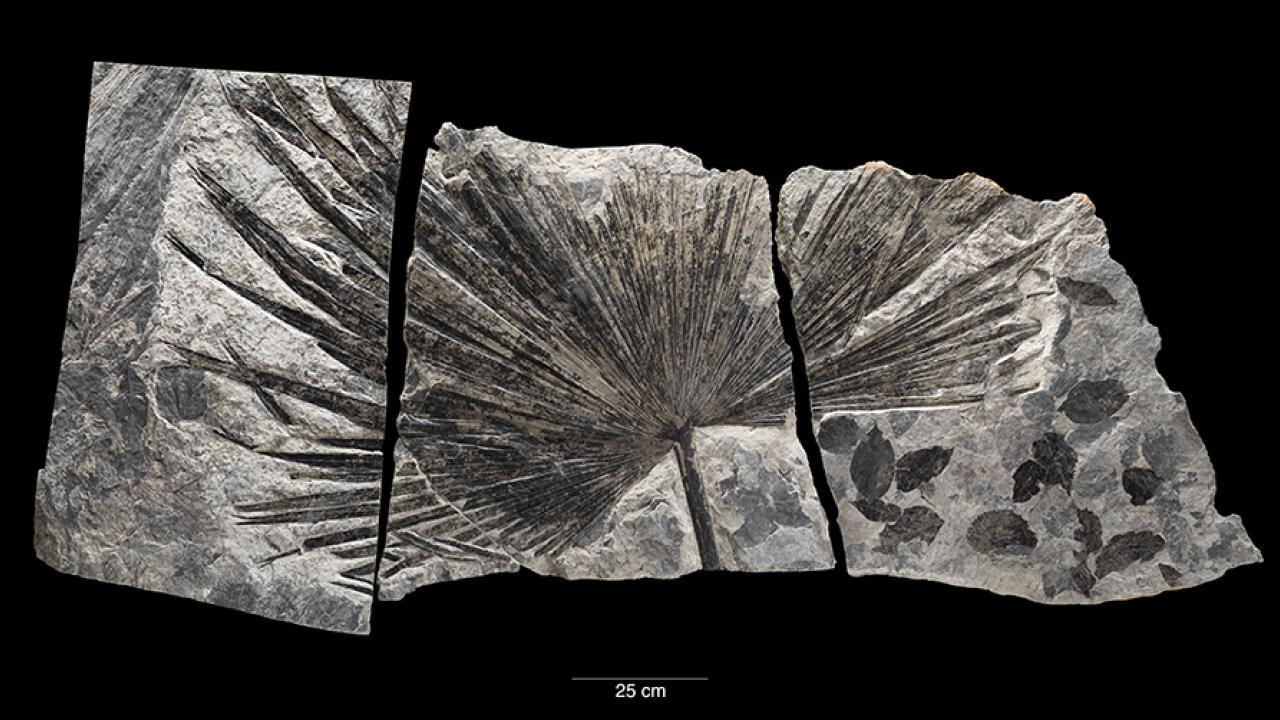

Palm trees in Alaska, crocodiles in Wyoming: Fossils show that Earth’s temperature has changed over hundreds of millions of years. Now a new study co-led by the Smithsonian and the University of Arizona, with Professor Isabel Montañez of the UC Davis Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, has produced a curve of global mean surface temperatures over the past 485 million years. The new curve, published Sept. 19 in Science, reveals that Earth’s temperature has varied more than previously thought as life has diversified, populated land and endured multiple mass extinctions. The curve also confirms that Earth’s temperature is strongly correlated to the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The team created the temperature curve utilizing an approach called data assimilation. This allowed the researchers to combine data from the geologic record and climate models to create a more cohesive understanding of ancient climates.

“This method was originally developed for weather forecasting,” said Emily Judd, lead author of the new paper and a former postdoctoral researcher at the National Museum of Natural History and the University of Arizona. “Instead of using it to forecast future weather, here we’re using it to hindcast ancient climates.”

Refining how Earth’s temperature has fluctuated over deep time provides crucial context for understanding modern climate change.

“If you’re studying the past couple of million years, you won’t find anything that looks like what we expect in 2100 or 2500,” said Scott Wing, the museum’s curator of paleobotany whose research focuses on the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, a period of rapid global warming 55 million years ago. “You need to go back even further to periods when the Earth was really warm, because that’s the only way we’re going to get a better understanding of how the climate might change in the future.”

The new curve covers most of the Phanerozoic eon, which spans 540 million years back from the present to the appearance of the first animal and plant fossils.

It shows that over the eon, global mean surface temperatures ranged between 52 and 97 degrees Fahrenheit (11–36 degrees Celsius). Periods of extreme heat were most often linked to elevated levels of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“This research illustrates clearly that carbon dioxide is the dominant control on global temperatures across geological time,” said Jessica Tierney, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona and a co-author of the new paper. “When CO2 is low, the temperature is cold; when CO2 is high, the temperature is warm.”

Earth now warming faster than ever

The findings also reveal that the Earth’s current GMST of 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius) is cooler than Earth has been over much of the Phanerozoic. But greenhouse gas emissions caused by anthropogenic climate change are currently warming the planet at a much faster rate than even the fastest warming events of the Phanerozoic. The speed of warming puts species and ecosystems around the world at risk and is causing a rapid rise in sea level. Some other episodes of rapid climate change during the Phanerozoic have sparked mass extinctions.

“Humans, and the species we share the planet with, are adapted to a cold climate,” Tierney said. “Rapidly putting us all into a warmer climate is a dangerous thing to do.”

The new paper is part of an ongoing research effort that began in 2018, when Wing, Huber and other Smithsonian researchers were helping develop the museum’s “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils—Deep Time.” The new hall aimed to put the museum’s fossils in context by highlighting how Earth’s climate has changed over the past half-a-billion years.

While the new paper is the most robust study of temperature change to date, the researchers expect that it will be refined as new clues are uncovered about the deep past.

Additional authors on the paper are Daniel Lunt and Paul Valdes of the University of Bristol. The research was supported by Roland and Debra Sauermann through the Smithsonian, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the University of Arizona’s Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in Integrative Science and the United Kingdom’s Natural Environment Research Council.

This article originally appeared on the UC Davis News website.